Time and Character encoding are the two things a programmer never wants to touch. Thankfully dealing with time has been made very easy, we developed ISO Standards, created standard libraries with good time functions and don’t have to worry until 2038 when a signed 32-bit integer is unable to hold the number of seconds elapsed since the Unix epoch.

Character encodings did not receive this kind of treatment until the emergence of Unicode but even then we still have massive issues when dealing with them.

History

If you don’t want to read through this history class I prepared, you can skip directly to the more interesting topic here: Encoding, Code Pages and Unicode for Programmers.

Electrical Telegraphy

One of the earliest encoding methods is Morse Code which was introduced in the 1840s. The earliest code used commercially was the Cooke and Wheatstone telegraph five needle code, aka C&W5, but no one really used it. Instead, each country went ahead and developed their own code leading to the creation of the American Morse Code:

1911 Chart of the Standard American Morse Characters from the American School of Correspondence

This code had issues so a fellow German named Friedrich Clemens Gerke developed a modified version in 1848 for use on German railways. At that time many central European countries belonged to the German-Austrian Telegraph Union and they quickly decided to adopt this version across all its countries in 1851.

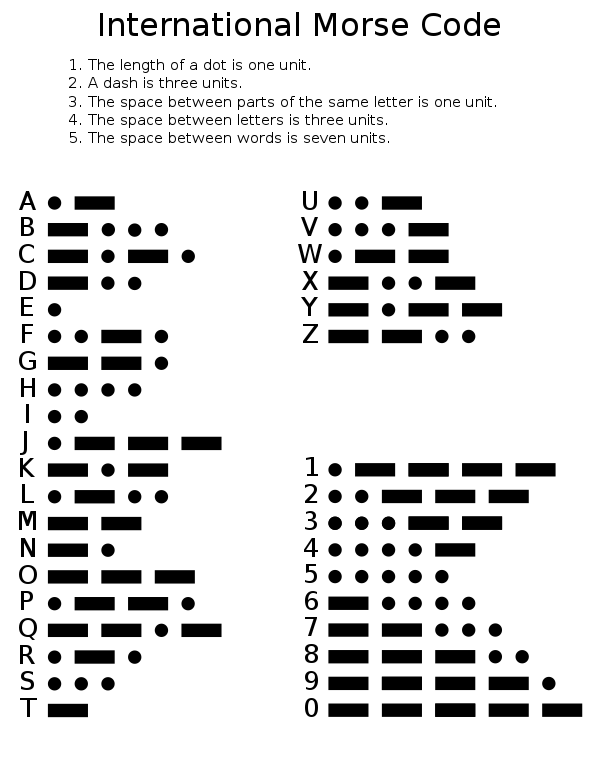

Due to the widespread use of the Gerke Code it became the International Morse Code in 1865:

Chart of the Morse code letters and numerals by Rhey T. Snodgrass & Victor F. Camp, 1922

Even though it is called the “International” Morse Code, US companies refused to adopt it and continued to use the American Morse Code. They didn’t want to re-train their operators and because the telegraph was not state controlled but multiple private companies worked together, they never adopted it.

So why am I telling you this 180-year-old story? Back then we already were unable to come to a consensus on what standard to use. The Gerke Code was adopted by the German-Austrian Telegraph Union, but each country developed their own Code at some point because they used special characters in their language. This has been the biggest problem throughout the years. In Europe, we mostly use Latin-based alphabets but over in Asia things looked different:

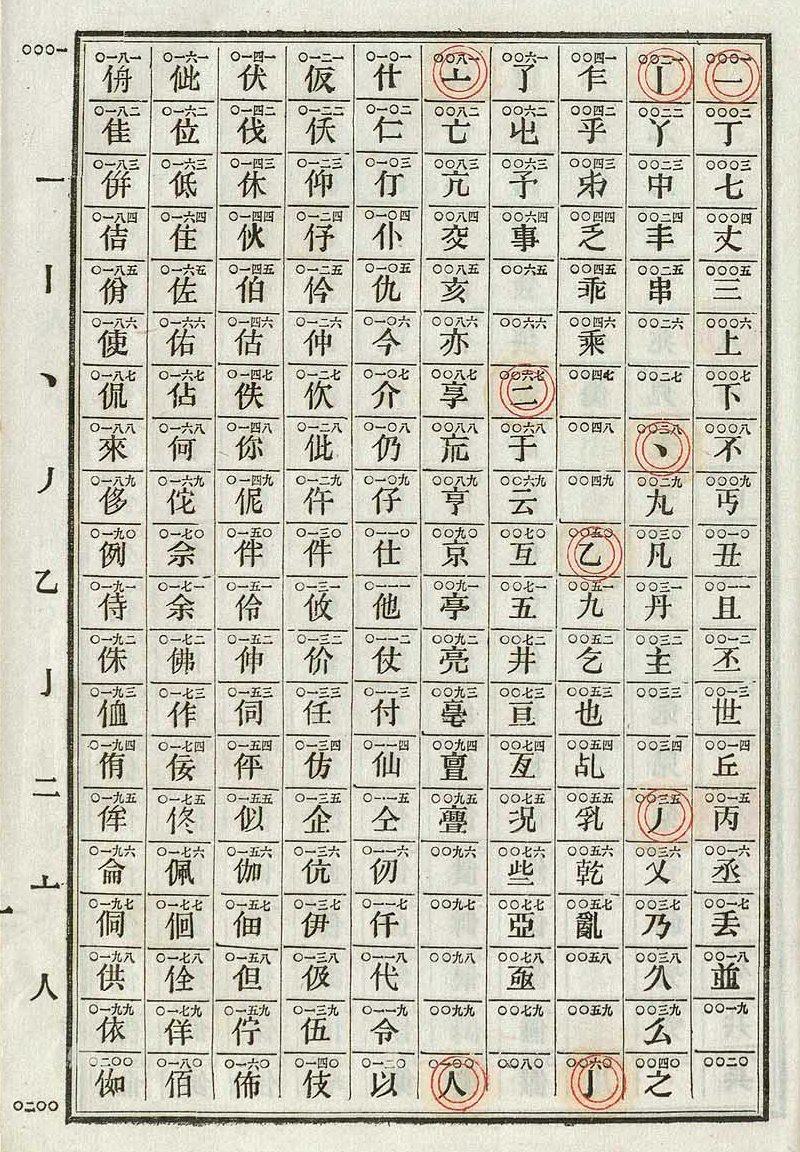

Obsolete Chinese telegraph codes from Septime Auguste Viguier’s New Book for the Telegraph

This is one page from the Chinese Telegraph Code book. There are nearly 10 thousand characters in this book.

This is another recurring theme across history. Languages use different alphabets or none at all. A Logography uses written characters that represent a word or morpheme, like Chinese characters. This makes creating encodings for use everywhere really hard because now you don’t have 26 letters in lower and uppercase and a few syntax characters, but thousands of characters that have their own meaning. Most of the technological advancements in telegraphy and digital computers happened in Europe or USA, Asia was often left out and new encodings would focus on Latin-based alphabets.

Automatic Telegraphy

In 1846 someone had the genius idea of automatically generating Morse code. Previously if you want to transmit a message, you’d go through each letter, look at the Morse Code table and press the required taps.

But what if you had a machine with multiple keys where each key corresponds to a different entry in the Morse Code table? A machine with multiple keys where each input corresponds to a different output, where have I heard that before? How about a piano:

Hughes Letter-Printing Telegraph Set built by Siemens and Halske in Saint Petersburg, Russia, ca.1900

Piano keyboards existed for a long time and are really easy to understand. If you want to transmit an A you just press the key that is marked with an A. No need to look into some weird table and get hand pain by pressing the same key in different intervals for the entire day.

But let us not get side-tracked by random history and focus on out main topic: encoding. With these new printing telegraphs the operator stopped sending dots and dashes directly with a single key but instead operated a piano keyboard and a machine which would generated the appropriate Morse Code Point based on the key pressed.

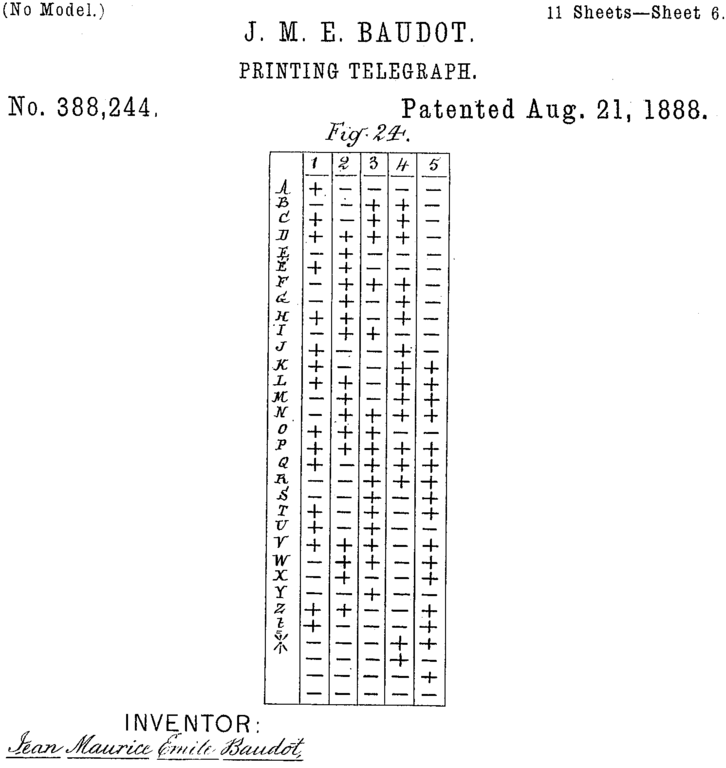

The Morse Code was designed to be used by humans meaning common letters were easier to “type” by requiring fewer inputs. In the 1870s Émile Baudot created a new Code to be used by machines instead of humans to make sending and receiving even easier:

Part of the patent from 1888 (US388244)

The Baudot Code is a 5-bit fixed-length binary code and next most important invention after the Morse Code. It is also known as the International Telegraph Alphabet No. 1 (ITA1).

If there is a No. 1, there must be a No. 2, so in 1901 Donal Murray modified Baudot Code to create the Murray Code. This code was used with punched paper tape. Now a reperforator could be used to make a perforated copy of received messages and a tape transmitter can send messages from punched tapes. Instead of directly transmitting to the line, the key presses of the operator would punch holes instead, making transmitting multiple messages from one tape very fast.

Operator fatigue was no longer an issue, instead Murray focused on minimizing machine wear and had to add control characters to control the machine. These characters are Carriage Return and Line Feed also known as CR and LF. If you every wondered where those came from, now you know.

In 1924 the International Telegraph Union created the International Telegraph Alphabet No. 2 (ITA2), based on Murray Code, which became the most widespread code as nearly all 20th-century teleprinter equipment used ITA2 or some variant of it.

1960s

ITA2 was very successful but we were going digital. Here are some inventions from this era to paint a picture: IBM created the IBM 704 in 1954 which was the first mass-produced computer with floating-point arithmetic hardware, the first transatlantic communications cable was laid down in 1956 and MIT and Bell Labs created the first Modem in 1959.

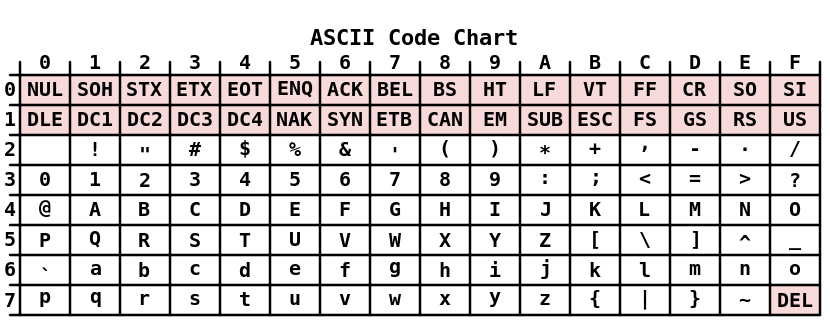

Things started to become digital and electronics became more important. Teleprinter technology also advanced and people wanted to use lowercase characters and additional punctuations. In 1964 the American Standards Association created the famous 7-bit ASCII Code also known as US-ASCII:

IBM and Code Pages

IBM with their mainframe computers played a very important role for us. They were a chief proponent of the ASCII standardization committee however they did not have enough time to prepare ASCII peripherals to ship with the IBM System/360 in 1964. This was a big problem and the company instead created the Extended Binary Coded Decimal Interchange Code (EBCDIC) which is an 8-bit character set.

The IBM System/360 was extremely successful and EBCDIC shared in this success. This was a problem, you now have ASCII which IBM really liked and EBCDIC which was used everywhere because everyone used the IBM System/360. Further complications arose since EBCDIC and ASCII were not compatible with each other which resulted in issues when transferring data between systems.

With EBCDIC came these new things called Code Pages. Not everyone speaks English and as we have seen before, some languages use a Latin-based alphabet, some use a non-Latin-based alphabet some don’t use an alphabet at all but Logography instead. Not only that but we are currently in the late 20th century when 20-megabyte drives costs 250 USD meaning we have to be space efficient.

For these reasons, IBM created code pages for the EBCDIC character set which are represented by a number and change the way you encode certain characters. One important thing I want to mention is that IBM created the code pages but not the standard that was behind it. As an example let’s look at JIS X 0201 which is a Japanese Industrial Standard developed in 1969 and was implemented by IBM as Code Page 897. IBM did not create the standard, they only created the code page that implemented it.

8-bit architecture

In the 1980s the 8-bit architecture led to the 8-bit byte becoming the standard unit of computer storage, so ASCII with its 7-bit length was inconvenient for data retrieval. Thus, in 1987 we got the standard ISO 8859-1 aka Extended ASCII which uses the extra bit for more non-English characters like accented vowels and some currency symbols.

Going Unicode

It is the year 1980 and a company named Xerox created the Xerox Character Code Standard (XCCS) which is 16-bit and encodes the characters required for languages using the Latin, Arabic, Hebrew, Greek and Cyrillic scripts, the Chinese, Japanese and Korean writing systems, and technical symbols.

A group with members of Xerox and Apple started thinking about a universal character set in 1987 and used the XCCS as an inspiration. This group quickly grew as people from Sun Microsystems, Microsoft and other companies started to join.

The Unicode Consortium which was incorporated in early 1991 published the first volume of the Unicode Standard later that year and the second volume in the next year to include a total of 28,327 characters.

Encoding, Code Pages and Unicode for Programmers

Now that the history class is over we can look at some code.

Windows API

If you ever wrote some C/C++ code and had to work with the Windows API you might wonder why there are multiple versions of the same function like MessageBox, MessageBoxA and MessageBoxW:

| |

The docs say A means ANSI and the W stands for Unicode, but this is a bit misleading so here is an explanation.

First ANSI is just straight up confusing and a “misnomer”.

A misnomer is a name that is incorrectly or unsuitably applied.

Microsoft themselves said it’s stupid:

ANSI: Acronym for the American National Standards Institute. The term “ANSI” as used to signify Windows code pages is a historical reference, but is nowadays a misnomer that continues to persist in the Windows community. The source of this comes from the fact that the Windows code page 1252 was originally based on an ANSI draft—which became International Organization for Standardization (ISO) Standard 8859-1. “ANSI applications” are usually a reference to non-Unicode or code page–based applications.

So going forward I’m just going to call it “Windows Code Pages”.

Next up is the W for Unicode. The W comes from wchar_t which is an implementation-defined wide character type. In the Microsoft compiler, it represents a 16-bit wide character used to store Unicode encoded as UTF-16LE.

So let’s recap:

MessageBoxA: accepts the 8-bitchartype and uses the Windows Code PagesMessageBoxW: accepts the implementation-defined widewchar_ttype and uses UTF-16MessageBox: just an alias that will use eitherMessageBoxAorMessageBoxW

The fact that wchar_t is implementation-defined is obviously a problem. Windows adopted Unicode when it fit in a 16-bit long type, but that is not the case anymore.

Now for some code and some experiments:

| |

The first two calls show what you’d expect to see as they only contain Latin characters. The other calls are more interesting. This hideous array initialization contains the bytes of “こんにちは” encoded in Shift-JIS. My system locale is set to “English (United States)” which means my Windows uses Code Page 1252 aka windows-1252. This Code Page does not contain any of the Hiragana characters and instead of seeing “こんにちは” on screen I get “‚±‚ñ‚É‚¿‚Í”. If change my system locale to “Japanese (Japan)” then Windows would use Shift-JIS aka windows-932 and display “こんにちは” correctly. The MessageBoxW call with L"こんにちは" correctly displays “こんにちは” because it’s UTF-16 encoded.

The Windows API also provides functions for converting between string types:

| |

With the first function we can convert our Shift-JIS encoded string into UTF-16 and correctly display it:

| |

Current Issues

We have looked at the history of character encodings and some examples with the Windows API. Now it’s time to take a look the issues we still have.

The Web is united under UTF-8 with over 98% of all web pages using it. This is further enforced by standards like JSON which require UTF-8 encoding. As good as this is, the desktops are still far behind UTF-8 adoption.

Windows started supporting UTF-8 with Windows XP but only since Windows 10 version 1903 is it the default character encoding for Notepad. These editors are the main culprits as they often default to the current Windows Code Page which makes sharing files internationally a pain.

Thankfully everything is starting to or already using UTF-8, newer languages like Go and Rust basically force you to use UTF-8 and even Microsoft said you should start using it.

Windows Code Pages are legacy but because it’s still used in production we continue to have issues with character encoding. If you have some issues I recommend trying Locale Emulator.

Closing Words

Props to you if you read this entire thing. I personally had to deal a lot with encoding issues as a lot of games I play come from Japan and don’t work on my machine without a locale emulator.

I hope this answered some questions you might have around this topic. It is very complex and has a very long history, but this should give you a peak into the issues we still have.