Edit (2023-01-20): This post got a lot of attention, so I want to clarify some things first. I’m a reverse engineering noob who hates EA with a passion. This blog post contains my personal, highly biased, opinions. If you want an unbiased description of the encryption used by EA Desktop, you can visit the GameFinder Wiki.

Background

Before I go in-depth on the encryption, I want to start by explaining the background of all of this:

I’m the developer of GameFinder, a .NET library for finding games installed via various stores. The library supports Steam, GOG Galaxy, the Epic Games Store, Origin and now also EA Desktop. In case you haven’t seen the news, EA is deprecating Origin and replacing it with their new program: “EA Desktop” or “EA App”. The old way of finding games installed via Origin doesn’t work for EA Desktop. This blog post will detail my 4-day journey of figuring out how I can support EA Desktop, which ultimately led to me reverse engineering and breaking its pathetic encryption.

Start of the journey

All of this began when I wanted to add support for EA Desktop. Origin had previously used manifest files to store information about installed games. These manifest files were located in C:\Program Data\Origin\LocalContent, however EA Desktop doesn’t create those files anymore.

I started by looking around in C:\Program Data and found a folder named EA Desktop:

C:.

│ machine.ini

│

├───530c11479fe252fc5aabc24935b9776d4900eb3ba58fdc271e0d6229413ad40e

│ CATS

│ IQ

│ IS

│ IS.json

│

├───6d13902b1570caf2c578d1f15fb1d5d9a2e62426246bc5eebea5707931ecdc21

│ CS

│ IQ

│

├───InstallData

│ └───Apex

│ └───base-Origin.SFT.50.0000848

│

└───Logs

EABackgroundService.log

We have some very ominous looking folder names, some installation data and a couple log files. However, notice that IS.json file? This is what started this rabbit hole, because it looks like this (you can view the full file here):

| |

When I found this file, I thought I was done already. This file contains everything I need for the library: the installation path, some identifier and the name of the game. I quickly wrote my implementation and send a debug build of my library to some testers that came back with this error message:

Unable to find IS.json inside data folder C:\ProgramData\EA Desktop

Turns out I’m the only one that has this IS.json file. Looking at the file dates, I noticed that it was created in early December 2022 and never touched again. I’m guessing some earlier version of EA Desktop created this file, but not anymore. Instead, it creates a file called IS in the same folder.

Analysis with CyberChef

Note: I will be using CyberChef throughout this blog post, if you want to follow along, you can download my encrypted file from GitHub and load it into CyberChef.

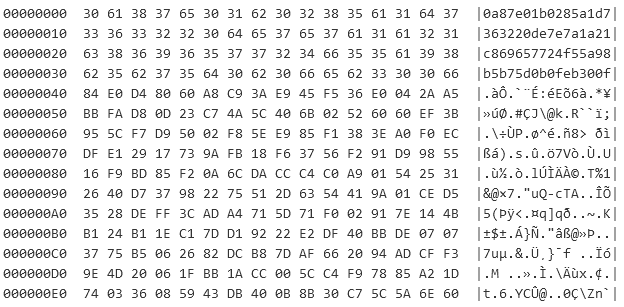

At this point I had no idea what I’m dealing with, so I grabbed the IS file and just looked at the Hexdump:

Hexdump of the first 240 bytes

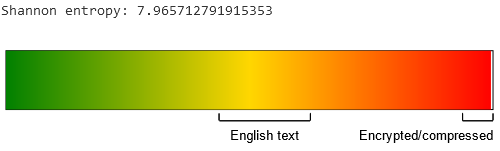

The file starts out with some kind of 256-bit hash, written as plaintext and the rest is just an incoherent collection of bytes. The Shannon Entropy is a good measure to identify if the input is structured or unstructured, and applying it on everything after the hash results in a value of 7.965:

Visualization of the Shannon Scale on the input

It’s safe to assume the contents are encrypted. Now we only have to figure out what algorithm and key were used.

Trying out everything

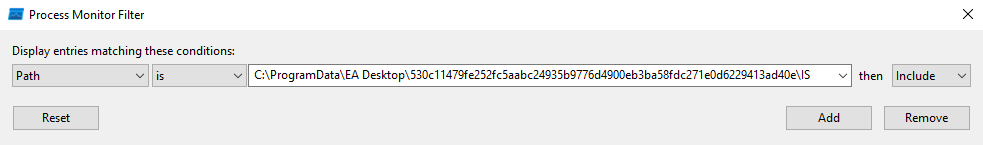

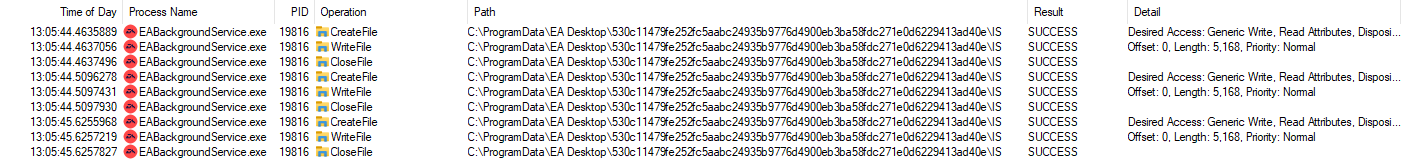

At this point I couldn’t do much without doing some reverse engineering. But before I can open up my favorite tool, I had to figure out what process even creates this file. Thankfully the Sysinternals Tools are amazing as always and provide the Process Monitor tool for monitoring file activity in real-time.

I noticed that the changed date of the encrypted file changes when I start or stop a download. Realizing this, I prepared a big download of Apex Legends, limited the download speed to 512kb/s and started monitoring with Process Monitor using this filter:

Adding a path filter to Process Monitor

With this filter activated, Process Monitor will only display entries where the path points to the encrypted file. After starting the monitoring and resuming and pausing the Apex Legends download a couple of times, I got these results:

Process Monitor results

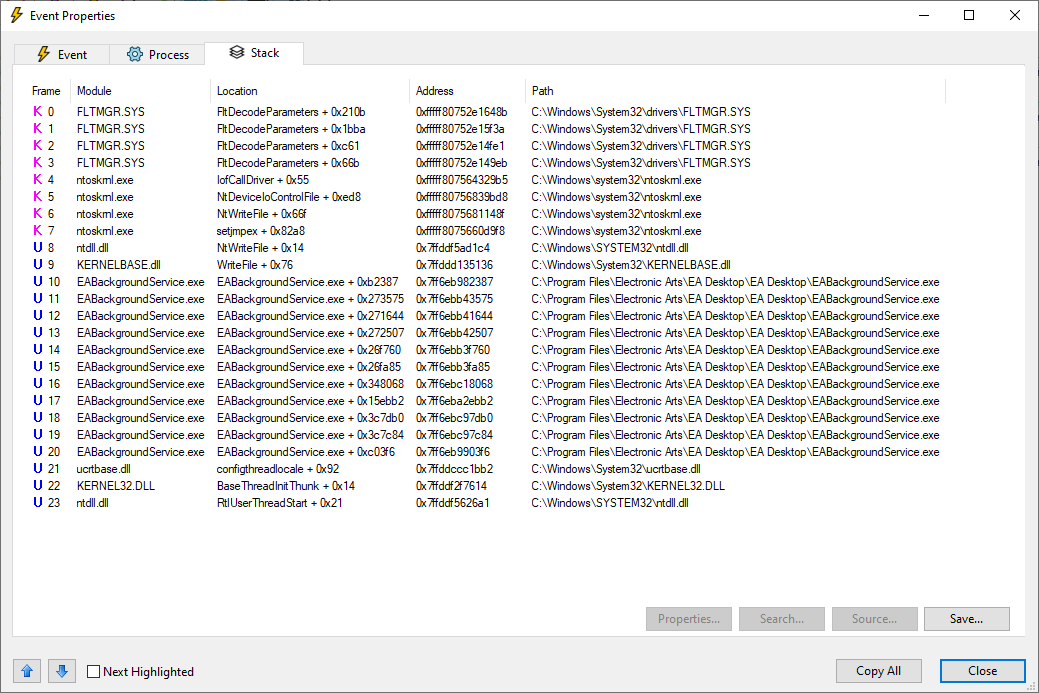

The process EABackgroundService.exe seems to be the only one that accesses those files. What’s even more impressive with Process Monitor, is the fact that you can double-click any of these entries and view the stack:

Stack of the first WriteFile entry

I now had everything I needed: the encrypted file, the decrypted file, the process that creates the file and multiple locations I can investigate.

Debugging and Reverse Engineering

Identifying the Algorithm

Note: I’m writing this blog post on 2023-01-18, the file version of EABackgroundService.exe is 12.85.0.5342 and its SHA256 hash is ba93d7a3a406128df5adc8f32322a897196eea83a6976b409dbd0e5401a612c8.

With the stack information from Process Monitor, I could start diving into the assembly code of the process. I used x64dbg to attach and debug the process and Ghidra to reverse engineering compiled code.

I started out by going up the call stack and looking at each function in Ghidra. The first couple functions were just wrapper functions around CreateFileW, WriteFile and other file system related stuff. However, the fourth function at EABackgroundService+0x271644 was a hit. Not only is this function massive, it references some interesting strings:

Saving [{}] into file: \n[{}]eax::services::localStorage::encryptDataToFile

I don’t think you can get more obvious than this. Turns out that excessive logging with inlined strings are really helpful.

I found an interesting function, now I only had to figure out what it does and where the encryption is being done. For this I don’t have any neat tricks up my sleeve, I just put a breakpoint at the start of the function in x64dbg and went through it step by step while also looking at the same code in Ghidra. I was mostly interested in the function parameters being passed, so I kept my eye on the RCX, RDX, R8 and R9 registers which are being used to pass parameters for the x64 calling convention.

It didn’t take me long to find a very interesting call at 0x270f26 with these parameters:

RCX: address of some region in memoryRDX: address of the plaintextR8: address to01B42F0E7E3B32E7C4251BC38FA2AE2EDB8DC26498E5B73E2A92AC9E8FFCB4F4R9: address to84EFC4B836119C20419398C3F3F2BCEF6FC52F9D86C6E4E8756AEC5A8279E492

This was very suspicious. After opening the function in Ghidra, I was very overjoyed to find this:

| |

Turns out that EA Desktop is using OpenSSL’s EVP functions to encrypt their files. In this case the file we need is encrypted using AES with a key length of 256 bits using the Cipher Block Chaining (CBC) mode.

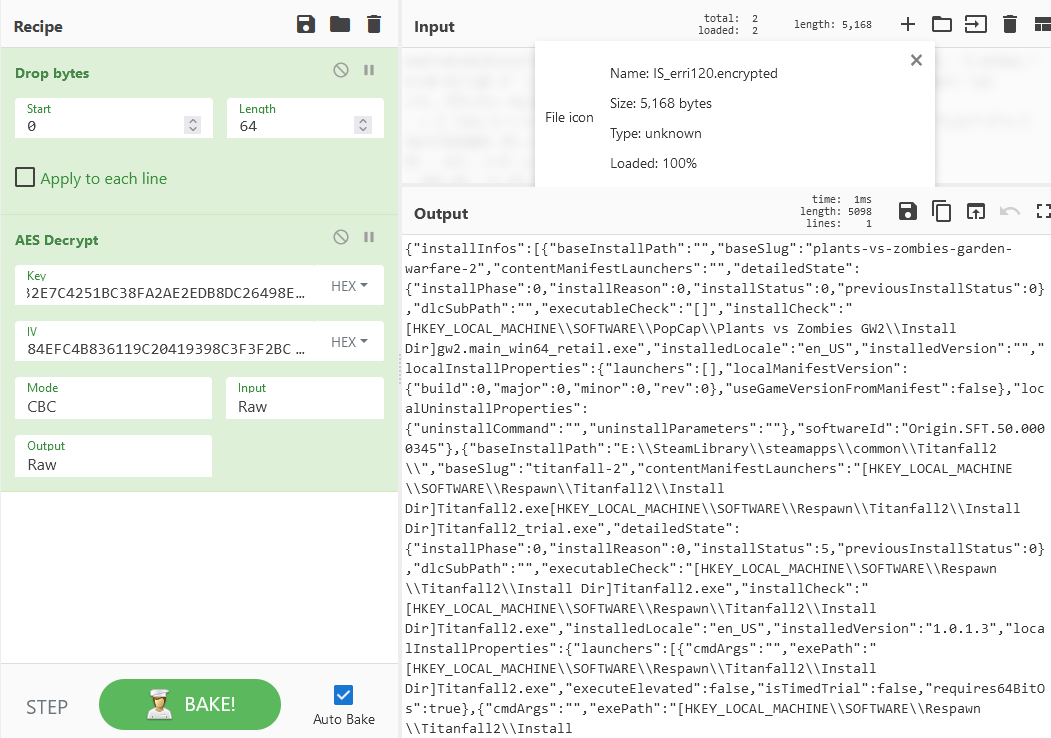

Using x64dbg, I just dumped the Key and IV from memory and used CyberChef to successfully decrypt the file:

Successful decryption in CyberChef

Recreating the IV

At this point I was very happy. I managed to identify the algorithm being used and was able to decrypt the file using the Key and IV from memory. The next step was figuring out how I can recreate them. You have to remember that my goal is to implement a method in my library, that can decrypt the file on its own, without requiring the consumer of the library to do anything special.

I started by following the parameters being passed to the encryption function. These values have to come from somewhere and I intend to find out where. Once again, I’m using x64dbg to step through the function and look closely at the registers. Now that I know what the Key and IV look like, I can identify the functions that create them or at least reference them.

And just as luck would have it, I found a function before the encryption function that accepts some curious parameters and outputs the Key and IV:

RCX: address of some region in memoryRDX: address of the stringallUsersGenericIdR8: address of the stringIS

Once again I investigated and after a bit of cleanup, the function essentially does this:

| |

These are wrapper functions for QCryptographicHash from Qt 5. CreateCryptographicHash is a wrapper for the constructor QCryptographicHash(QCryptographicHash::Algorithm method) where they always pass SHA3 256 as the algorithm and AddDataToHash is a wrapper for addData(const char *data, int length).

If you’re like me, and you see this, then you quickly head over to CyberChef, input allUsersGenericIdIS and create the SHA3 256 hash to get THE IV as output: 84efc4b836119c20419398c3f3f2bcef6fc52f9d86c6e4e8756aec5a8279e492.

THE IV NEVER CHANGES: It’s always SHA3_256("allUsersGenericId" + "IS"), a fucking constant.

As a quick side note: remember 530c11479fe252fc5aabc24935b9776d4900eb3ba58fdc271e0d6229413ad40e? This is the folder name of the file IS. This is also a SHA3 256 hash (CyberChef):

SHA3_256("allUsersGenericId") = 530c11479fe252fc5aabc24935b9776d4900eb3ba58fdc271e0d6229413ad40e

I have no idea where this allUsersGenericId comes from, but some genius at EA thought it would be a good idea to include this in almost every hash.

Recreating the Key

Anyways, we have the IV. Now the remaining part is figuring out how to recreate the Key, which turned out to be more involved than the IV.

The function that creates IV did some more stuff afterwards. They reset the SHA3 256 hash instance and added some very interesting data to it: allUsersGenericIdISa2a0ad25aa3556c035b34ea63863794e54ad5b53 (CyberChef)

SHA3_256("allUsersGenericIdISa2a0ad25aa3556c035b34ea63863794e54ad5b53") = 01b42f0e7e3b32e7c4251bc38fa2ae2edb8dc26498e5b73e2a92ac9e8ffcb4f4

This is the key we previously dumped from memory. Let’s break this down: "allUsersGenericId" + "IS" + "a2a0ad25aa3556c035b34ea63863794e54ad5b53". The first two parts are already known to us, they are the components of the IV. The last part a2a0ad25aa3556c035b34ea63863794e54ad5b53 is more interesting. This looks like another hash, but it only has a length of 160 bits. Once again we can use CyberChef to analyze this hash:

Hash length: 40

Byte length: 20

Bit length: 160

Based on the length, this hash could have been generated by one of the following hashing functions:

SHA-1

SHA-0

FSB-160

HAS-160

HAVAL-160

RIPEMD-160

Tiger-160

Based on the previous results, I’m assuming this is a SHA1 hash, since that’s the only one that OpenSSL supports.

Edit (2023-01-20): Someone on reddit informed me that OpenSSL also supports RIPEMD. My statement was a bit misleading, as SHA1 was the only algorithm from that list that was imported from OpenSSL, not supported. I just looked at the imports in Ghidra and found that SHA1 was the only match, so I went with it, and it turned out to be correct.

With this information in hand, I decided to try going the opposite way and start with the import of EVP_sha1 and look at what references this. Turns out there is only one function that uses this:

| |

I aptly named this function HashSomething as it appears to be some sort of general purpose hashing function that takes some input, the output buffer and probably an enum to control which hashing algorithm should be used. This looked very promising, so I went back to x64dbg, put a breakpoint at the start of the function and inspected the input, only to find this:

| |

Using CyberChef to verify my assumption, I was very happy to find out that this is the missing component:

SHA1(hardwareInfo) = a2a0ad25aa3556c035b34ea63863794e54ad5b53

They hash the hardware info using SHA1, then combine that hash with the constants allGenericId and IS to create the Key.

Hardware Information

In order to replicate the hardware info hash, I needed to figure out which components and which properties went into it and where they are getting the information from. On Windows, the best way to do this, is to use the WMI. I’ve never used the WMI, so I just checked out an example to find the library functions I need to look out for. These include CoInitialize, CoCreateInstance and CoSetProxyBlanket, just to name a few. With that newly found information, I went back into Ghidra and went up the call stack of the general purpose hashing function to find something that looks good.

I ended up in a function that was being called by the function that creates the IV and Key. However, I noticed that there was a big fat static initialization being done. Turns out that they collect your hardware information when the process starts and then never again. Using x64dbg to restart the process and I stepped through the static initialization to figure out what was going on.

After a rather tedious process of continuously looking at register values until something made sense, I managed to extract every class and property name used to create the hardware info:

Win32_BaseBoard Manufacturer=ASRockWin32_BaseBoard SerialNumber=(string with lots of whitespace)Win32_BIOS Manufacturer=American Megatrends Inc.Win32_BIOS SerialNumber=To Be Filled By O.E.M.Win32_VideoController PNPDeviceId=PCI\VEN_10DE&DEV_2486&SUBSYS_147A10DE&REV_A1\4&2283F625&0&0019Win32_Processor Manufacturer=AuthenticAMDWin32_Processor ProcessorId=178BFBFF00A20F10Win32_Processor Name=AMD Ryzen 7 5800X 8-Core Processor(also had a lot of whitespace at the end)

You can try this out yourself by using the wmic tool:

| |

But we’re not done yet. There is one value missing: 7CB7433E. This is the hex value of the serial number of the volume associated with the root directory of your C:\ drive. It is returned by GetVolumeInformationW. Note that this a different serial number from the one obtained by Win32_PhysicalMedia SerialNumber:

This function returns the volume serial number that the operating system assigns when a hard disk is formatted. To programmatically obtain the hard disk’s serial number that the manufacturer assigns, use the Windows Management Instrumentation (WMI) Win32_PhysicalMedia property SerialNumber.

Conclusion

graph TD

allUsersGenericId & IS --> allUsersGenericIdIS[allUsersGenericId + IS]

hardwareInfo[Hardware Information] --> |SHA1| hardwareInfoHash[Hardware Info Hash]

allUsersGenericIdIS & hardwareInfoHash --> combine[allUsersGenericId + IS + Hardware Info Hash] --> |SHA3 256| KEY

allUsersGenericIdIS --> |SHA3 256| IV

This flowchart shows the complete process of generating the Key and IV. With those values, you can easily decrypt the file using AES 256 CBC.

Let’s go back to the point of all of this: finding out which games are installed. I did all of this just to decrypt a file that contains some installation paths to EA games. I don’t understand why this file is encrypted in the first place. It doesn’t make any sense. You encrypt a file because it contains sensitive information and/or you want to keep it from prying eyes. Now the question is “who is not supposed to read this file”? The fact that they created the plaintext version of this file at some point but later changed it on purpose means they don’t want anyone to read it.

And this isn’t even all, if you look at the flowchart, you will realize that if the user changes a single hardware component of their PC, the Key will be different, and you won’t be able to decrypt the file anymore. The team at EA that implemented this and the person that made the decision to encrypt the file in the first place, have no idea what they are doing. This is a pathetic attempt to prevent users from reading this file.

I have demonstrated how easy it is to “break” the encryption using tools like CyberChef, x64dbg and Ghidra. The “encryption” used by EA Desktop is straight up pathetic and useless. In the off chance that anyone from the team that works on the program is reading this: just write the plaintext file, there is no point in encrypting it.

For me personally, this has been a very fun adventure. I managed to make good progress every day and got more experience using the tools listed above and assembly in general. I can also now finally have support for EA Desktop in my GameFinder library, so users can stop pinging me about it.

Edit (2023-01-20): After this post got a lot of attention on r/ReverseEngineering, I want to add some more information. As you may have noticed from the tone of this post or the edit I added at the start: I hate EA with a passion. As with my last blog post related to reverse engineering, I only dive into Ghidra as my last resort when everything else fails, and I’m very frustrated.

At the start of the post, I showed you the contents of the folder of the IS.json file. This folder contains three encrypted files: CATS, IQ and IS. In this blog post, I’ve only talked about the IS file, because it’s the only relevant file for me, the author of GameFinder.

Let’s talk about those other files: CATS contents and IQ contents. Once again, these files contain no sensitive information. You can decrypt them using the same method as before, just replace allUsersGenericIdIS with allUsersGenericId{fileName} when creating the hashes.

These file names are also a bit weird, so let’s change that:

CATS: catalog itemsIQ: installation queueIS: installation state

All of these files are encrypted using the same generic function. They of just dumping the plaintext to a JSON file and calling it a day, someone had the genius idea of encrypting them. After people read my blog post, they asked the obvious question: “Why encrypt these files?”. I can’t tell you. While working on my GameFinder library, I looked at similar files from Steam, GOG Galaxy, the Epic Games Store and even Origin, the precursor of EA Desktop, and all of those files were stored in plaintext. You can head over to the GameFinder Wiki, click on any store and find out how they store their files. Everything is stored as text, they don’t even do binary serialization or anything fancy. EA Desktop is the only one that sticks out and encrypts their files.

All of this, for what? I honestly think they just want to fuck with 3rd party game launchers and force users to use their new app. But that is just my highly biased opinion as someone who hates EA with a passion :)